A Few Minutes Of Slow

The joy--and pain--of homemade pasta and the sourdough process.

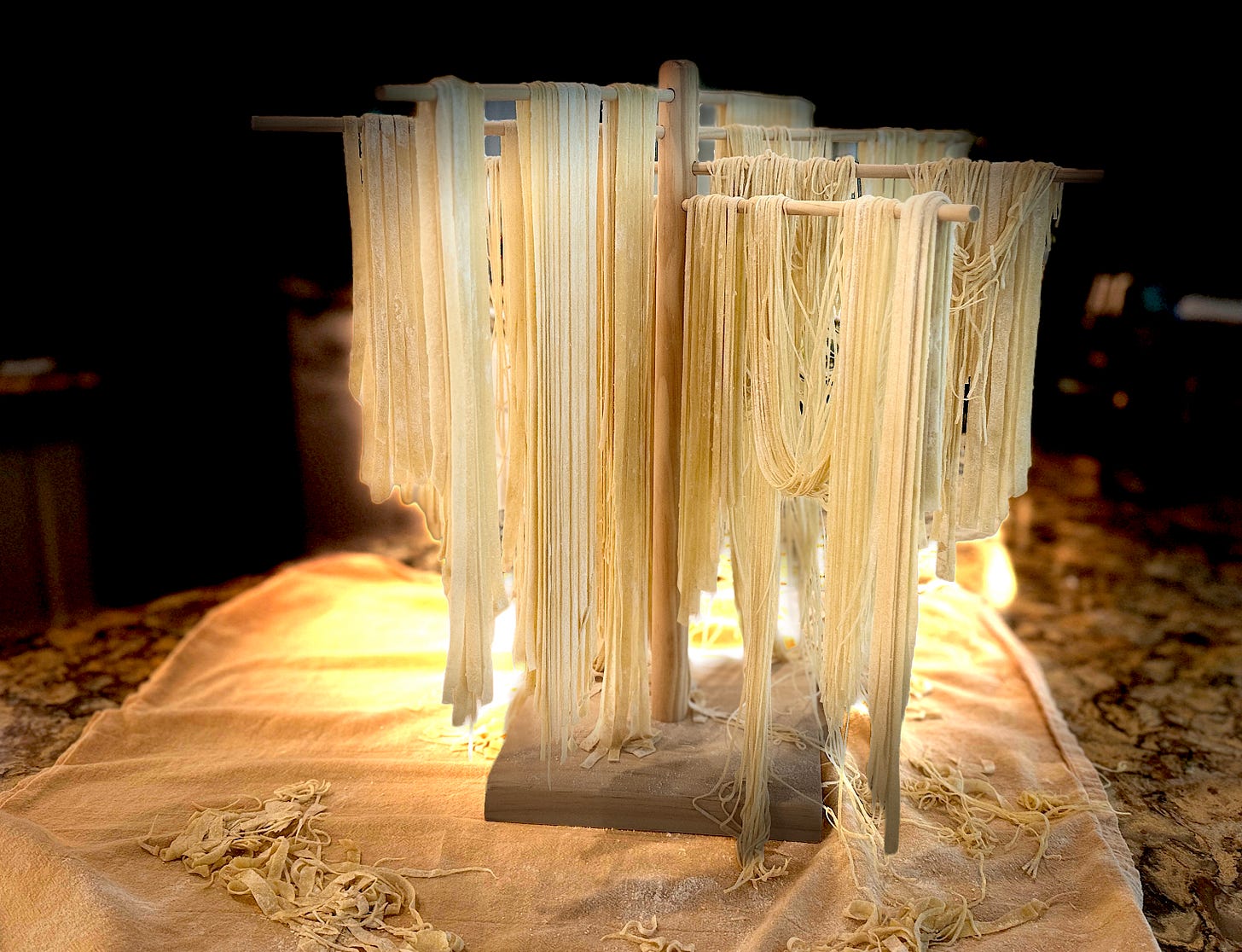

It takes a couple of hours, it’s hard on the back, and two pairs of hands are necessary to pull this off: a lovely rack of slowly drying homemade egg pasta, made from ancient wheat (most of our current wheat strains have been modified radically for more rapid growth, far greater yeilds, and for certain types of pest resistance), organically grown.

My husband and I have made this several times now, and it always turns out spectacular. Today, having found a recipe where I could use up some sourdough discard in the process intrigued me, so I decided to make up another batch.

I’ve been working with sourdough now for about five years. Slowly, with many mistakes, dead ends and some very strange outcomes, I grew my own starter, i.e., my personalized leavening agent, and have kept it alive all this time.

It seems mysterious, but it is actually not—this is how bread has always been made. The invention of a commercialized, dried form of yeast only appeared in the 1800s, but the nature and purpose of yeasts have been known for thousands of years. Wine, beers, bread, cheeses, yogurts—anything fermented makes use of it. It’s everywhere—on everything, floating around you, endless variations.

“Starter” is nothing but flour and water, preferably mixed by hand, that sits around for a week to ten days, each day with some poured out (the “discard”), and fresh flour and water and a little hand work thrown in until it develops its lovely bubbles and glorious sourdough smell.

Take a small portion of this out at night, mix it with around 4-5 times as much water and flour, cover it, and in the morning, it is ready to flavor and leaven anything you might want to mix with it. I generally make a traditional sourdough with only three ingredients: water, flour, and salt. I call it my “Trinitarian” loaf. It’s easy, delicious, and I’ve yet to give a loaf away that didn’t leave people raving about it.

But the variations are endless, and I’ve not found any limits as to bread possibilities IF, and here’s the big IF, one is willing to embrace the patience that comes with sourdough and IF one is willing to recognize that the starter is a living organism and needs attention to stay healthy.

Which is where the discard comes from. If, like our ancestors through the centuries, bread-baking is a regular, daily activity, the starter will get all the attention it needs. After taking some out for the fresh loaves, the remainder is “fed” fresh water and flour, and it sets about fermenting once more to create a fresh supply. It’s the closest thing to an infinite source of food possible—as long as it is appropriately maintained, portions of it can be given away for as long as there is bread to bake and people around to enjoy it.

But . . . in our world, where bread has taken on a bad reputation (and there are good reasons for this perpetuated by many commercial bakeries), families are smaller, schedules tighter, and pressure greater, few engage in the slowness and hands-on engagement that truly delicious bread demands.

It is rare for even the most dedicated home bakers to do this daily. Even so, the starter needs regular attention to stay healthy, so some of it must be periodically poured off, i.e., the discard, and fresh flour and water mixed back in.

So, I’ve always got two apothecary jars of starter, one fed and one unfed, sitting in my refrigerator. And the unfed jar was full to the top.

Which leads me to today’s pasta making—I had stumbled across a recipe using sourdough discard in an egg noodle recipe. We’ve been making homemade pasta for a few years now. Once I discovered that I could eat the ancient grains without any digestive concerns, making my own was a logical next step.

But what I didn’t want was a pasta-making machine, any more than I want a giant stand mixer or a special bread-baking machine. Not only do heavy machines take up too much space, but they also, for me, drain the joy from the process. To work the dough by hand, to understand the process of gluten formation, to recognize how weather affects the outcomes and timing, and to master the manipulation necessary to get a good texture that will hold air, rise properly, and cook or bake perfectly, all bring me an almost undefinable joy and sense of peace.

And yes, it is a pain to do. I’m not able to manipulate the hand-cranked pasta machine myself, so it is something my husband and I do together. Actually, it is something my husband, I, and our dog, Remy, do together as Remy has discovered the delicious flavor of the egg noodle bits that land on the floor. OK, I’ve been guilty of nibbling on them too—before they land on the floor.

I also know that to engage in this slow, meditative, extraordinarily satisfying way of providing basic sustenance has become nearly impossible for most of us. Would I like to live in a time with a much slower pace of life, but that also is absent the many conveniences of modernity that bring such comfort and delight?

A deep, honest breath here. The answer is no. Even so, I suspect I achieve a greater and more profound connection with the Holy One, and far more powerful insight into the nature of life and death, of giving and receiving, from learning to work with sourdough than from multiple years of study.

But if you ever want to try it, you’ll never regret it.

When is our invitation for dinner??? I enjoyed reading this post. I'm impressed!

I want to make sourdough bread.😀